Viola palmata L. (pro. sp.)

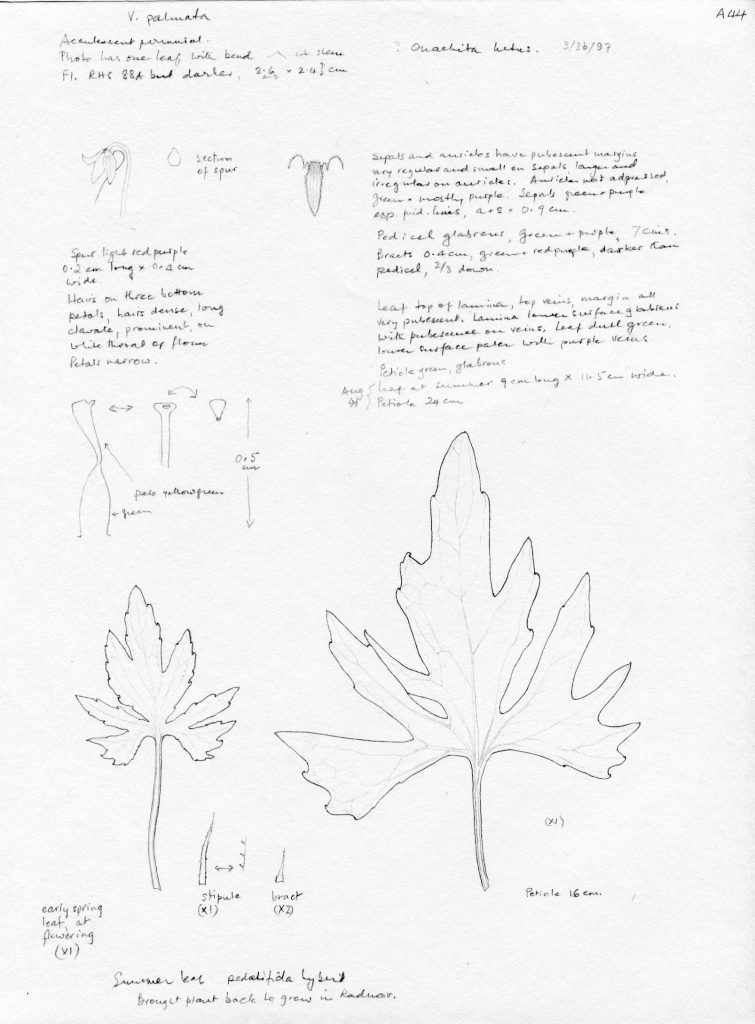

Kim’s unedited notes. Illustrations: 14 photographs of Viola palmata and xpalmata, 2 pencil drawings

Viola xpalmata = V. sagittata x V. sororia.

Sp. Pl.:933. 1753

(syn. V. esculenta Elliott, V. triloba Schwein., V. viarum Pollard, V. stoneana House, V. chalcosperma Brianerd, V. langoisii var. pedatiloba Brainerd).

TM: Section Nosphinium, subsect. Boreali-Americanae [NEW classification, 2010].

2N=54 (x10), IPCN 94-95, Hill, L.M., 1995.

Plants in Missouri and Arkansas appear to be hybrids with the pubescent form of V. sororia because they are so pubescent. The triloba type hybrids must be with the smooth form of V. sororia as parent.

Seeds dark grey, 1.8 x 1.0mm.

Seeds Denver BG shiny, dark grey, 1.8 x 1.0 mm.

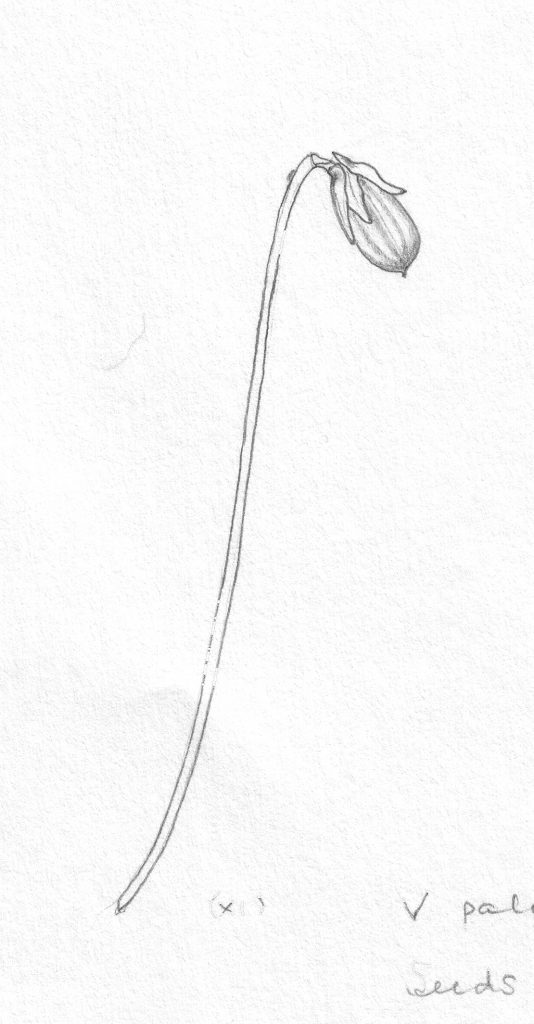

Seed pod drawing C87: pod green, glabrous, seeds dark brown (?mature) 1.6 x 0.9 mm.

Harvey Ballard, July 2005 & Michigan Botanist, 1994:V. xpalmata produces leaves early in the growing season and in the fall that are undivided (cf. V. xsubsinuta with early spring and late fall leaves are divided). They are both nothotaxa, the product of hybridization in this case between V. sororia and V. sagittata. V. xpalmata also grows on moist diabase (low in calcium, but neutral pH). However, plants in Missouri and Arkansas were growing on limestone, with chert/flintstone in one area in Missouri (Rock Bridge Memorial State Park, Columbia, Missouri).

www.missouriplants.com, written and photographed by the late Dan Tenaglia, in Alabama (friend of Carol Lim):V. triloba [V. palmata] is just one of the many small purple-flowered violets you are sure to encounter in the Missouri woods. When young, this plant is difficult to tell apart from other violets, such as V. sororia, but as the plant mature its leaves will become lobed. V. triloba is found mostly in the southern half of the state and prefers acidic soils (???). Dry rocky open woods, thickets, bluffs, Flowering – April – May. [as these plants are V. sagittata x sororia then the preference for acid soil makes sense, these photos of leaves show early leaves not divided. Photographs taken at Rock Bridge State Park, Columbia, MO., 4-17-04 [see i-photo viola file].

Plants with divided leaves grow in places with more sunlight, in clearings or edges of woodlands. The more divided the leaf, the more sun is needed.

V. palmata alba seeds dark grey to black, 1.6 x 1.0 mm

f. alba x ‘Freckles’ seeds speckled dark grey, 2.0 x 1.2mm. Seed from JVS 6191 ARGS ’92.

This ‘species’ is a can of worms. From my observation of all the species that come under this general name, I have come to the conclusion that all the divided leaf species, with the probable exclusion of Viola pedata, and all the undivided leaf species of blue-purple flowered stemless violas are probably involved in a massive hybridization process. Where ever any of these species meet in the wild, they will cross. Depending on the parent species involved, the crosses and backcrosses, the resultant characteristics vary. Evolution in progress? See paper by Erben. ‘The significance of hybridization on the forming of species in the genus Viola. Bocconea 5(1) – 1996.

From my article for NARGS bulletin: Three species of blue stemless violas have divided leaves: Viola sagittata, Viola palmata and Viola pedata. The first two have flowers closely resembling those violas with undivided leaves, while Viola pedata has distinctly different flowers. Viola sagittata is a pubescent plant, with long, narrowly ovate leaves gradually tapered to the tip, and short side divisions at the base. There is a smaller subspecies, Viola sagittata ssp. ovata, which used to be called Viola fimbriatula. It differs from the species by a shorter, wider, ovate leaf, shortly narrowed to the tip, and shorter or no divisions at the base. It grows in drier locations. The leaves of Viola palmata are more evenly and deeply divided into from three to many lobes. Actually, this ‘species’ is a taxonomic can of worms, enveloping Vv. brittoniana, egglestonii, esculenta, lovelliana, septemloba, stoneana, triloba, viarum, so for the time being it probably should be called Viola Xpalmata and wait for changes, but don’t hold your breath—it will take years of DNA analysis to disentangle this melange. The degree of pubescence is very variable in different plant communities. The two species and one subspecies described all have violet-purple flowers with a white center, obvious fine, straight hairs on the inside of the lateral petals, and a few, less obvious hairs on the lowest petal.

From Harvey Ballard: ‘The “Viola palmata” melange is badly mangled by most specialists and taxonomists, and does NOT, in my studies since 1979, deserve wholesale lumping as has been done increasingly, lately. I’ve made studies of most of the taxa in the field and herbarium, and much much more needs doing. A good 10-year, intensive study across all of eastern North America, including reciprocal transplant and common garden studies, intensive genetic analysis, and exhaustive statistical studies, will be the only way that the stemless blue violets including V. “chasmatina” and many others will be clarified adequately. I’ve made smaller, regional studies over the last two decades, but without larger funding and a much more rigorous approach, little more can be done that will amount to anything (anything believable, anyway). Thomas (Marcussen) wouldn’t have the time or money to do much with these critters at this point. Once again, I’ve been developing preliminary data to submit a large grant to initiate studies of the lobe-leaved taxa, including V. viarum, V. egglestonii, V. pedatifida, V. brittoniana and V. septemloba initially, but it will be a year or two before I can finish up the preliminary studies to be sure I can do what I say I’m going to in resolving issues in these species/hybrids/variants. The V. chasmatina actually resembles more closely the morphology and ecology of limestone-loving V. viarum in the southeastern Great Plains region, and less so V. nuevo-leonensis of eastern Mexico.’

July, 2005: Harvey said that V. viarum is glabrous and lime-loving, as is V. egglestonii. He thinks that during one of the geological periods the prairies were much more widely spread to the east, and that V. brittoniana, xpalmata(?? should this read V. subsinuata?) and egglestonii are hybrids of V. pedatifida (the prairie species) left behind from this period.

Kim to Harvey: Would it be possible to devise a study that analyses/compares the chromosomes of V. ‘chasmatina’, V. pedatifida, nephrophylla, missouriensis, sororia, xviarum, egglestonii, V. brittoniana and V. septemloba? This would sort out a lot of the problems of this mix-up.

Harvey 5 Feb 09: The only approach that I think will be wholly successful in clarifying variation and hybrid or non-hybrid origins, and species limits, in any of the stemless blues will be a combination of extensive field collections over the range of every species possibly involved in a species complex; greenhouse or growth chamber or common garden transplant experiments with hundreds or even thousands of plants from every taxon, and possibly even controlled crosses; and genetic studies using molecular markers. It’s really several PhDs worth of work, to do the whole group right, and at least one 4-5 year PhD just to do the Palmata complex. They all have precisely the same chromosome number, and hybrids are mostly fertile and also proliferate cleistogamous seeds. Brainerd showed that any interspecific hybrid he brought in from the field produced “stable” and morphologically uniform hybrid segregates within 3 generations. (This seems to have eluded all readers.) What that means, at least to me, is that any hybrid form that finds a well developed habitat in a local or regional area can become fixed morphologically and genetically within 3 or a few generations and then will breed true as if it were a normal species. That’s actually my hypothesis for the earlier origin of many “species” in the group, besides the obvious ones; and it’s pretty unusual among vascular plants that plants apparently of hybrid origin can behave like normal species so quickly.

So, the tricky part is that studies really have to be extensive in sampling over the range of each potentially involved species, they have to provide enough detailed information to reject alternative explanations, and they have to be comprehensive enough to convince all biologists of the results. So far, not a single study has ever managed to do those things for me until now, at least for most species. And genetic data is really key to all of it, which makes it more costly and time consuming to do it right. But, I’m still looking for people to potentially start it.

The herbarium specimens of Big Bend N.P., Guadalupe Mountains N.P. and Sul Ross University have been combined into one data base. No viola species in Big Bend herbarium collection. In Sul Ross, there are collections of Viola purpurea from the area around Hunter Peak, under yellow pines (left turn at the top of Bear Canyon), Guadalupe Mountains National Park. There are also collections of V. missouriensis, V. lovelliana (now calling this V.’chasmatina’) and one collection sheet of Viola guadalupensis (type specimen).

There are two specimens of V. lovelliana collected from the Guadalupe Mountains, both labelled V. palmata (syn. lovelliana). The first collected in South McKittrick Canyon, 18 May 1958, 6500 ft. The second collected in Upper Pine Spring Canyon, 3 May 1947, 7000ft.

INVENTORY OF THE FLORA OF THE GUADALUPE MOUNTAINS, NEW MEXICO AND TEXAS [SECOND WORKING DRAFT] [MARCH, 2002]. Compiled by: Richard D. Worthington, Ph.D. Floristic Inventories of the Southwest Program, P. O. Box 13331, El Paso, Texas 79913.:

VIOLA PALMATA L. Early Blue Violet [Viola viarum Pollard; V. lovelliana E. Brainerd] [Gehlbach, 1965; Russell, 1965; Fletcher, 1980a; Burgess & Northington, 1981; Spellenberg et al., 1986; Hayes, 1988; McKinney, 1992; Worthington, 1999b] [Patterson 501: TEX-LL] [Knight 1822, 1823: UNM] Note: The above name has been assigned to a violet in moist canyons at higher elevations. One investigator is of the opinion it is an undescribed species related to some Mexican taxa. The study of its relationships is in progress.

Atlas of the Flora of the Great Plains:

Viola triloba Schwein. var. dilitata (Ell.) Brainerd has been collected from Cherokee County, Kansas, Jasper County, Missouri and Ottawa County, Oklahama. It occurs infrequently on the Great Plains.

Viola viarum Pollard occurs in a narrow bank in the south east of the Great Plains, along the Missouri River, from the se corner of South Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri. It is also further east of the Great Plains in the states of Missouri, three counties on the eastern border of Oklahoma and two counties of western Arkansas. Why is it confined to this narrow band? Moisture? It is within the same distribution as the downy Viola sororia. Also same distribution as V. pedata and V. sagittata. ??? We need to use chromosome markers to see how these species are related. Also Viola pedatifida is in this range, but covers a far greater area, especially to the north, but not so far into the south in Oklahoma and Arkansas.

V, Xpalmata (syn. V. triloba [see McKinney, above ].– those at Walnut Run north side are pedatifida x sororia = xsubsinuata.)

Growing on diabase at 322 site, see comments about soil under V. pubescens, conspersa or cucullata. As this hybrid is of difference origins and very widely spread, this soil type information may not be as relevant as a comment for this species. [I think it is, the pubescent xpalmata plants at Walnut Run north side are pedatifida hybrids especially after reading comments below]. Grows where there is a little more moisture , ie on the sides of the pathway at Walnut Run.

www.enoriver.org/eno/parks/PennysBend/pennysbend.htm

The unique plants of Penny’s Bend grow in soils derived from the diabase rock. These soils (Iredell on uplands and Wilkes sandy loam at the base of the slopes) are quite different from typical Piedmont soils. Unlike surrounding acidic or sour soils which have a low pH, Penny’s Bend soils are basic, or sweet, with a high pH. Sweet soil is ideal for certain kinds of plants typically found in other regions of the United States, particularly in the prairies of the Midwest, including Indigo, Lithospermum canescens and Viola pedatifida hybrids. These V. xpalmata plants had short (1-1/2 cm long) horizontal rhizomes and were growing on the uplands (Iredell?).

www.discoverlife.org/nh/cl/ONF/plants.html Georgia Botanical Society

Viola palmata grows in these four habitats within the Oconee National Forest, Georgia

- B-OAK-HICKORY FOREST

- C-OAK-PINE FOREST

- D-PINE BARRENS, or PINE PLANTATIONS

- G-ROCK OUTCROPS

May 5, 2009: Haycock Mountain, in northern Bucks County, is a ridge of volcanic diabase. Most of the walk will be rocky woods, with plants such as Cimicifuga racemosa, Obolaria virginica, Hepatica, Rubus odoratus, and Cornus alternifolia. In a field of large boulders we will see Adlumia fungosa and Sambucus racemosa … and V. Xpalmata (photographed) and V. pubescens var. scabriuscula (no photos).

State Game Lands 56, which has a moist meadow containing a number of interesting plants, including a good-sized population of Aristolochia serpentaria. Photographed V. Xpalmata, and hirsutula flowers, V. sororia, V. adunca minor and V. Xsubsinuata?? See other notebook. Not diabase here at this location.

Directions: From Doylestown, take PA Route 611 north. At 1.2 miles north of Ottsville, the road forks; take the left branch to get onto Durham Rd/PA-412. Follow this road for 0.5 miles, then turn left onto Mountain View Dr/PA-563. After 1.2 miles, turn right onto Top Rock Trail. After 0.6 miles, where the road bends to the right, pull into the parking lot on the left. The lot has no sign visible from the road, but once you are in the lot, you will see a sign saying “Welcome, Hunt Safely.” To get directions from Mapquest or other on-line service, use the address 200 Top Rock Trail, Kintnersville, PA.