Viola pedatifida. G. Don

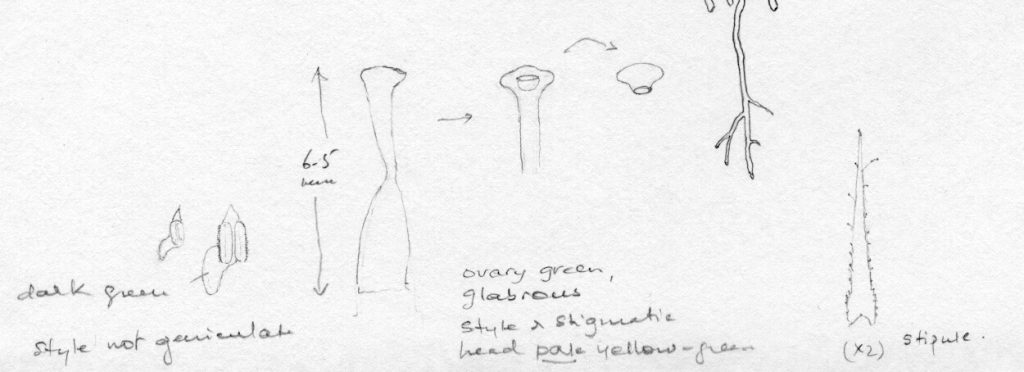

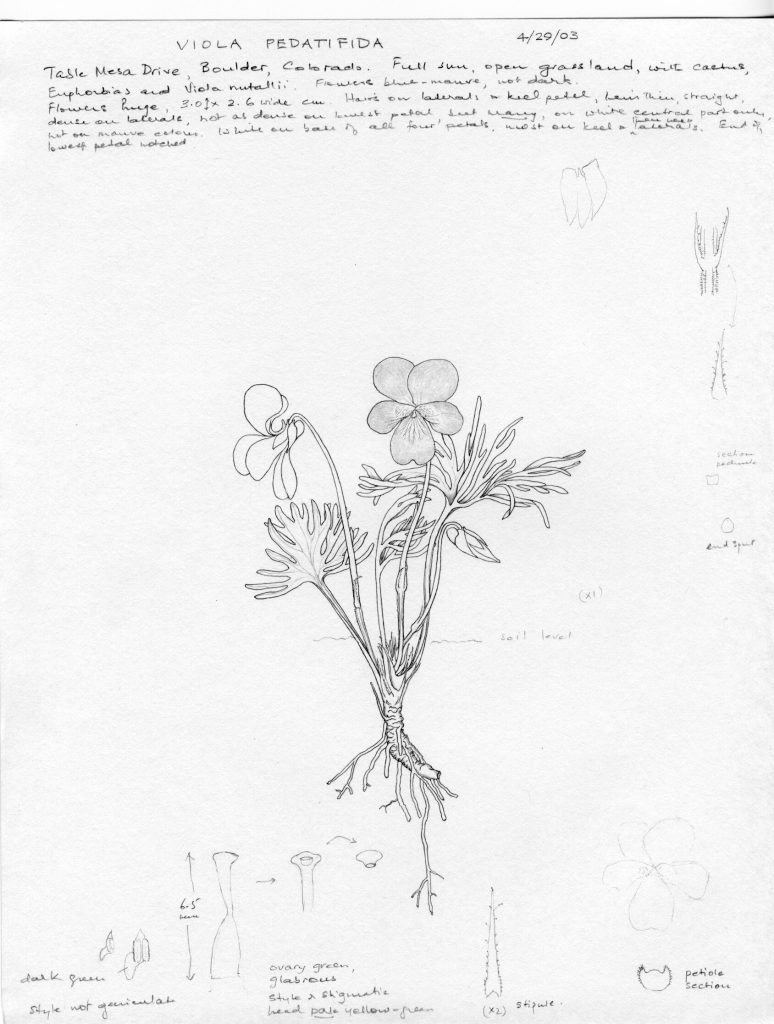

Kim’s unedited notes, 3 photographs and 3 drawings of Viola pedatifida (including one of Kim’s original pencil drawings)

Boreali-Americanae.

George Don, 1798-1856.

‘pedatifida’ means pedately divided.

Viola pedatifida G.Don — Gen. Hist. 1: 320. 1831 (GCI)

Viola pedatifida G.Don — Gen. Syst. i. 320. (IK)

Viola pedatifida G.Don var. bernardii Greene — Pittonia 3: 259. 1898 (GCI)

Viola pedatifida subsp. brittoniana (Pollard) McKinney — Sida, Bot. Misc. 7: 22. 1992 (GCI)

Viola pedatifida G.Don subsp. brittoniana (Pollard) L.E.McKinney — in Sida, Bot. Misc., 7: 22 (1992):. (IK)

Viola pedatifida G.Don var. indivisa Greene — Pittonia 5: 124. 1903 (GCI)

V. pedatifida always grows in alkaline soil.

Found on outwash mesas east of Boulder, gambel oaks (Quercus gambelii), ?ponderosa pine +/- Douglas Fir (Pseudotsuga menzesii), open parkland ecosystem

Range: Colorado and New Mexico to Saskatchewan and Illinois.

New Mexico: Sierra Grande; between Park View and Tierra Amarilla. Plains and low hills, in the Upper Sonoran Zone. Hybridizes in northern New Mexico with nephrophylla, leaves divided only about half way to the base, see also Ezra Brainerd. V. pedatifida leaf blades lobes, lobes of leaves linear or nearly so, numerous, extending nearly to base.

The presence of V. pedatifida at 7,500 ft, Mongollan Escarpment, Coconino Co., central Arizona in pine forests is remarkable as this species belongs mainly to prairies east of the Rocky Mountains.

So much written about pedata but not much about pedatifida. The habitat of pedata is preserved/encouraged by road building, removal of roadside trees, removal of competition, clearing and exposing of roadside banks (but problem with weed spraying) whereas for habitat of pedatifida has been most destroyed by agricultural use of land.

2n=54. IPCN: Love A. & D. Love, 1982.

Seeds pale to mid brown, 2.0-2.2 x 1.2 mm.

Seeds AGS 5885, pale cream brown, 2.2 x 1.1 mm.

Seeds SRGC 4264, pale to dark brown, 2.2 x 1.1 mm.

Seeds ex Carol Lim, ex Sunlight gardens, mid to dark brown, small colourless elaiosome, 2.1-2.3 x 1.0-1.1 mm, my #1274.

Seeds ex HR in NARGS seed exchange labelled V. delphinantha and corrected to V. pedatifida by NARGS before we got the seed is not the same as above, it is pale grey speckled with dark grey,1.8 x 1.0mm, my #1275.

[Mature seeds of V. brittoniana are very pale brown! 1.5-1.6 x 1.0 mm. Elaiosome absolutely clear or colourless, small. Collected in New Jersey, 5 yds past 2-mile post on Clarke’s Landing Road, on RHS. V. pedatifida seeds are larger, 2.2 x 1.1 mm; pale to dark brown. V. septemloba seeds are dark brown]. NO cleistogenes (like V. pedata!)

Weber says V. pedatifida occurs infrequently on the mesas of Colorado front range, flowering in early spring. Table Mesa Drive, on the outwash from the mesa, near Boulder, Colorado. As the road curves around to the right just above the school, beyond the last house close to the road there is a gravel path that diverges somewhat from the road (to the right). On the left side of this path there is a little remnant of native vegetation and this is where the violets are. You don’t have to walk a hundred yards. Probably not out yet, the season has been so late (May 10, 1995). [On limestone, also with Vv. nutallii and scopulorum at the same site, but the latter is further from the road]. Another site: Davidson Mesa, which is the hill you climb going south toward Rocky Flats after leaving the junction of the road to Eldorado Springs, just above the irrigation ditch it hides among the rocks.

Correspondence with Rebecca Day-Skowron, in Colorado: V. pedatifida should be flowering April to early May at the latest. I was too late in May and June. Just starting to flower on April 29, in Boulder, and not up yet in area where Kim and Bernie live NE of Castle Rock.

Flint Hills, east Kansas, tall grass prairie Nat. Reserve, Chase Co.

Nelson, R.A. Handbook of Rocky Mountain Plants. 1969. Dale Stuart King, Tucson, Arizona: V. pedatifida is a dark purple-flowered, acaulescent species with much dissected leaves which occurs on the high plains and reaches the lower slopes of the foothills in Colorado, and New Mexico.

KEY:

1a. Flowers yellow; petals may be purple-tinged on back.

1b. At least some of the leaves deeply or shallowly lobed or toothed.

1c. Some leaves shallowly lobed or toothed …………………………….. Viola purpurea

2c. All leaves deeply, palmately lobed …………………………………….. Viola sheltonii

2cc. None of the leaves lobed or deeply toothed

3c. Leaves longer than wide …………………………………………………….. Viola nuttallii

3cc. Leaves rounded, heart-shaped at base …………………………………… Viola biflora

1aa. Flowers white, blue or purple

2b. Plants leafy stemmed.

4a. Flowers blue …………………………………………………………………….. Viola adunca

4aa. Flowers white or nearly white

5a. Flowers entirely white; leaves with rounded tips ………………… Viola palustris*

5aa. Flowers with purplish tinge on back of petals …………………. Viola canadensis

2bb. Plants acaulescent

6a. Leaves not dissected ………………………………………………….. Viola nephrophylla

6aa. Leaves deeply, palmately dissected into narrow divisions …. Viola pedatifida

* Reference says V. pallens but this is incorrect.

Viola pedatifida grows in Canada, according to USDA map, Alberta, Seskatchuan, Ontario and … see USDA site.

http://www.inhs.uiuc.edu/~kenr/Prairieist.html

List of plant species at three natural blacksoil prairie remnants in Central Illinois, Kenneth Robertson, Center for Biodiversity, Illinois Natural History Survey, 607 East Peabody Drive, Champaign, IL 61820 USA:

Prior to settlement by people of European descent, more than 60% of the land area of Illinois was in prairie vegetation, more than 22 million acres. Some counties in Central Illinois were more than 90% prairie. Today, only about 2,300 acres of high quality, unplowed prairie remains in Illinois, mostly in very small, isolated remnants. Three noteworthy examples so such remnants are: Loda Cemetery Prairie Nature Preserve in Iriquois County, Prospect Cemetery Prairie Natural Preserve in Ford County, and Weston Cemetery Prairie Nature Preserve in McLean County. These prairies are all mesic blacksoil prairies, about 5 acres in size, all originally pioneer cemeteries established on virgin prairie.

The soil that developed under blacksoil prairies is one of the most agriculturally productive soils in the world, and very nearly all prairies were plowed. Viola pedatifida grows in all three of these mentioned cemeteries.

‘An uncommon Colorado native’ on-line catalogue of Rocky Mountain Rare Plants nursery of Rebecca Day Skowron (and ?husband Bob Skowron, who took a fabulous photo of it, on their website, taken at Raven Ranch, April 2000). Having seen it later in Boulder, just starting to flower on April 29, 2003, the environment did not look the same as Bob Skowron’s photo. It was growing in the dead remains of grass from the previous year’s growth. It is a plant of open grasslands. At Kim and Bernie’s [surname?] place, it grows under the gambel oaks and out from the shade into the grassland. They live NE of Castle Rock, CO, at Franktown. Is this Pierre Shale? Ask, or get the CO Roadside Geology book again.

Roadside Geology of Colorado, Halka Chronic: Mesas south (and north) of Boulder are parts of mountain pediments eroded in upturned Cretaceous sedimentary (limestone?) rocks and later covered with 10 to 20 feet of younger gravel. Though scarcely consolidated, gravel makes a caprock because its permeability inhibits runoff and therefore prevents erosion.

The site of Viola pedatifida is in the out-wash from Table Mesa on limestone rocks.

From the distribution map in the Atlas of the Flora of the Great Plains, Viola pedatifida occurs predominantly on the eastern side of the Great Plains. [North and South Dakota, Minnesota, Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and a few counties in NE Oklahoma]. The atlas does not mention the areas of the eastern foothills of Colorado. The distribution of this species has probably been greatly disturbed by agriculture. Distribution not restricted by cold, as it continues into Canada in the Great Plains, and is in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado. This small population in Colorado is disjunct from the concentration of specimens collected on the eastern side of the Great Plains, not continuous through the middle of the Great Plains like Viola nutallii. [The close-up photo I have of V. pedatifida from the Osarks in sw Missouri is quite acceptable to use for publication. Compare this with the images on Google of Viola pedatifida.]

This is a grasslands plant. Must mention this word, and/or prairie.

Peterson Field Guide: The difference between Viola brittoniana species and V. pedatifida is that the latter is not coastal, flowers are paler, leaf lobes are very narrow.

www.enoriver.org/eno/parks/PennysBend/pennysbend.htm

Diabase is a type of igneous rock that forms when molten rock intrudes into cracks and fissures below the earth’s surface. The sill is the actual structure of the igneous intrusion, in this case, a horizontal layer of diabase rock. This sill was formed about 225 million years ago when the continents were separating to form the Atlantic Ocean. The intrusive volcanic rock is hard and very resistant to erosion, compared to the surrounding Triassic sedimentary rocks. Consequently, the Eno River is deflected and turns southward, flowing around the diabase backbone of Penny’s Bend. As the Eno encounters softer material, it flows eastward, and finally, northward, forming the eastern boundary of the Preserve. The unique plants of Penny’s Bend grow in soils derived from the diabase rock. These soils (Iredell on uplands and Wilkes sandy loam at the base of the slopes) are quite different from typical Piedmont soils. Unlike surrounding acidic or sour soils which have a low pH, Penny’s Bend soils are basic, or sweet, with a high pH. Sweet soil is ideal for certain kinds of plants typically found in other regions of the United States, particularly in the prairies of the Midwest, including Indigo, Lithospermum canescens and Viola pedatifida hybrids.

www.mnr.gov.on.ca/MNR/nhic/documents/winter9697.html

Ontario Natural Heritage Information Centre: NEWSLETTER Volume 3, Number 2, Winter 1996/1997 We haven’t heard of any native plants being added to the Ontario flora in 1996, although there were a number of exciting rediscoveries and range extensions. While leading a Field Botanists of Ontario (FBO) outing in May, NHIC Community Ecologist, Wasyl Bakowsky, found a small population of Prairie Violet (Viola pedatifida, G5S1). The only previous Ontario record was a collection made by John Macoun in 1907 from Brantford, the same area where Wasyl made his find.

V. pedatifida grows on the alkaline soils of the prairies of the mid-west. As these soils are the best for agricultural cultivation, most of the habitat of the native species supported by this alkaline soil have declined or been wiped out. Only small pockets have survived. This environmental change has wiped out the insect species dependant on the prairie plants, for example the Regal Fritillary Butterfly (Speyeria idalia).

Prairie Violet (Viola pedatifida G. Don)

Identification: Leaves basal and flowers on separate stems. Flowers light violet-blue. Leaves deeply cut into narrow, linear segments, each segment typically bifid or trifid at its apex.

Distribution: Found primarily in the plains region of central North America, extending eastward to Ohio and Arkansas.

Habitat: Prairies of the western parts of eastern North America.

Flowering period: April to June.

Similar Species: Prairie Violet is similar to Birdfoot Violet, but the leaf lobes are narrower and the apices of the lobes more deeply divided into bifid or trifid lobes. The prairie habitat is distinctive. V. brittoniana occurs along the coastal regions of eastern North America, not on the prairies.

Restoring the Regal Fritillary Butterfly (Speyeria idalia) and its host plant (Viola pedatifida) at Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge. Dr. Diane Debinski; Professor of Animal Ecology; Iowa State University. Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge, located just 25 minutes east of Des Moines, Iowa, was established in 1990. Its mission is to re-construct tallgrass prairie and restore oak savanna on 8,654 acres of the Walnut Creek watershed and to provide a major environmental education facility focusing on prairie, oak savanna, and human interaction.

Dr. Diane Debinski and her students are continuing to work toward reintroduction of the prairie endemic butterfly, Speyeria idalia, the Regal Fritillary butterfly to the Refuge. Prairie restoration efforts have the potential to provide new habitat for this rare species. Experimental plots have been established to test hypotheses regarding the use of various management techniques (fire, grazing, and control) to restore Speyeria idalia’s host plants (Viola pedatifida). The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation has approved a grant of $31,000 for NS NWR in order to begin this project. Preliminary results indicate that the violets are responding more favorably to burning than to the control treatment. Data is not yet available for effects of grazing on Viola pedatifida. Once these plantings are established, Speyeria idalia will be reintroduced to the experimental plots. Burning treatments will then be curtailed.

www.gpnc.org/regal.htm The caterpillars of Regals, as is true of most fritillaries, eat only violets. In particular, Regals prefer the Birdsfoot Violet (Viola pedata) and Prairie Violet (V. pedatifida). The eggs are laid in late summer. The newly hatched caterpillars overwinter and begin eating the following spring. The adults emerge in early summer and may be seen through September. The known range of the Regal Fritillary originally stretched from Maine to Montana and south to Oklahoma and North Carolina. Because the caterpillars utilize the prairie species of violets, this species was never found outside tall grass prairie. Regals have almost disappeared from their former range east of the Mississippi River. They now occur only from southern Wisconsin west to Montana and south to northeast Oklahoma. Some relict populations occur in Pennsylvania and Maryland but they may not last much longer.

Restoring the Regal Fritillary Butterfly (Speyeria idalia) and its host plant (Viola pedatifida) at Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge. Dr. Diane Debinski; Professor of Animal Ecology; Iowa State University.

Dr. Diane Debinski and her students are continuing to work toward reintroduction of the prairie endemic butterfly, Speyeria idalia, the Regal Fritillary butterfly to the Refuge.

Literature for range of V. pedatifida:

Arizona: Kartesz, J.T. 2002. Atlas of the Arizona flora. Unpublished; Kearney, T., and R.H. Peebles. 1960. Arizona flora with supplement.

New Mexico: Martin W.C. & C.R. Hutchins. 1980. A Flora of New Mexico. V. pedatifida is shown as present in one county only.

Why has the Regal Fritillary gone into such a sharp decline?

| Habitat loss is a definite possibility. The greatest decline in Regal populations was noticed over the last 40 years, so conversion of prairie to farmland is probably not to blame because most of that occurred before that period. Suburban sprawl has definitely had an impact on relict prairies during that time, however, and maybe that is a factor. | |

| Another possibility is disease. Captive populations being kept for reintroduction purposes have been hit by a virus that is transmitted from parents to young. If this is active in the wild populations, that would be a serious matter. | |

| Could chemicals in the environment be to blame? The disappearance of the Regals coincides with the onset of widespread use of herbicides and pesticides in agriculture. No such relationship has been established, but the overlap of the two trends is suggestive and should be investigated. One thing that does not help is the haphazard egg laying behavior of Regals. Most butterfly mothers will lay their eggs directly on the host plant that the caterpillar will consume. Regals, however, just wander around laying their eggs throughout their grassland habitat rather than directly on or next to the violets that the caterpillars will need. Then, the caterpillar will hatch before winter, but not begin feeding until the following spring! This extremely risky strategy may explain why a Regal female may lay up to 2,400 eggs – which is far more than most butterfly females will lay.

The butterflies probe each flower for nectar with their proboscis. Look for interaction between them and other insects that come to the flowers. Butterflies can be quite pugnacious sometimes, and quite tolerant of other insects at other times. Regal Fritillaries can be seen all summer long in the right habitat. If you see them, you know that you are in a high-quality tallgrass prairie – a remnant of what used to be the most extensive habitat type in North America, but which is now much reduced in area.

Prairie Violet Description: This native perennial plant is about 3-6″ tall. It consists of a rosette of basal leaves, from which one or more flowering stems may emerge that are somewhat taller. The basal leaves have a deeply lobed palmate structure, and are rather fan-shaped in appearance. They are up to 1″ across and have petioles up to 1″ long. The flowering stems are more or less erect, but curve abruptly downward where the flowers or buds occur. These flowers are about ¾” across and quite similar in appearance to other violets. They have 5 petals that are blue-violet or pale blue-violet, and 5 green sepals that are long and pointed, but remain behind the petals. The two upper petals are more or less rounded, but sometimes they are rather elongated. The lower side petals have white hairy beards at the throat of the flower. At the base of the lower center petal is a patch of white with fine lines of purple that function as nectar guides to visiting insects. The Prairie Violet usually blooms from mid- to late-spring, but it can also bloom during the fall under favorable conditions. There is no noticeable floral scent. During the summer months, inconspicuous cleistogamous flowers mature into seed-heads that are brown and triangular-shaped. These release little brown seeds by mechanical ejection, which can fall to the ground several inches away from the mother plant. The root system is fibrous, and can form rhizomes. Cultivation: The preference is full sun and mesic conditions. Some shade from grasses and other plants later in the year is normal and tolerated. The soil should have the capacity to retain some moisture during summer dry spells, preferably with high organic content. This plant can be difficult and short-lived if a site doesn’t satisfy its requirements. Range & Habitat: Prairie Violet is an uncommon plant in the northern half of Illinois, and rare or absent in the southern half. Habitats include mesic to slightly dry black soil prairies, savannas, and loess hill prairies. It is not normally encountered in disturbed or developed areas, but can be considered an indicator plant of high quality prairie remnants. Occasional wildfires are probably a beneficial management tool, as this removes much of the brush and dead debris that can smother these little plants. Faunal Associations: Little information about flower-visiting insects is available for this species of violet, but similar violets attract Anthophorine bees, Mason bees, Eucerine Miner bees (Synhalonia spp.), Halictine bees, small butterflies, and Duskywing skippers (Erynnis spp.). Syrphid flies also visit violets, but they feed on stray pollen and are non-pollinating. Because these insect visitors are uncommon during the spring, the Prairie Violet is capable of self-fertilization, like many other violets. The caterpillars of various Fritillary butterflies feed on this and other violets, including Euptoicta claudia (Variegated Fritillary), Speyeria cybele (Great Spangled Fritillary), Speyeria aphrodite (Aphrodite Fritillary), Speyeria idalia (Regal Fritillary), Speyeria diane (Diana), and Boloria selene myrina (Silver-Border Fritillary). The small size and early growth habit of this plant provide some protection from mammalian herbiovres. Photographic Location: The photograph was taken at Loda Cemetery Prairie in Iroquois County, Illinois. |

Smithsonian herbarium has isolectotype:

Viola brittoniana Pollard, C.L., Bot. Gaz. 26 :332. 1898 – Isolectotype (Violaceae)

COLLECTION: Britton, N.L. s.n., 21 May 1893. USA. New York. Staten I.

COLLECTION REMARKS: Also a type of Viola atlantica Britton (non Pomel, 1874) in Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 24:92. 1897.

LECTOTYPIFIED BY: McKinney, L.E., Sida Bot. Misc. 7. 1992

CURRENT PLACEMENT: Viola pedatifida subsp. brittoniana (Pollard) McKinney (Violaceae)

VERIFICATION: Specimen compared to the original publication.

US SHEET NO.: 00007346 BAR CODE: 00479254

www.dickinson.edu/prorg/pabs/vascular_plants.htm V. pedatifida is listed as threatened in PA.